Topics About Fake News

Settling on a collective definition for “fake news” is challenging because perspectives naturally differ among members of the two main political parties in the United States. Bovet and Makse (2019) defined fake news as “fabricated information that disseminates deceptive content, or grossly distorts actual news reports, shared on social media platforms” (p. 2).

Before looking into how falsehoods spread online, it is important to note why an examination of this issue is critical. The full extent of Russian interference—or, as Jamieson (2018) called it, Russia’s “cyberwar”—remains challenging to determine with precision.

After reviewing the literature on the issue, several common research methods and communication theories emerged. Prior research studies have involved conducting message system analysis, or content analysis, of Facebook posts and tweets that researchers deemed fake or deliberately misleading.

Theory can help provide answers about why people share fake news. Festinger (1957) defined cognitive dissonance as the psychological state in which our beliefs contradict our attitudes or actions. To restore balance, we need our beliefs and attitudes to be consistent. One way to achieve that is through confirmation bias.

With more than 2 billion active users, Facebook plays a unique role in aiding the spread of information, as well as disinformation, as it curates and customizes what we see and read on the social media platform. The Frontline episode “The Facebook Dilemma” blamed the proliferation of fake news on the company’s proprietary algorithm, which ranks and displays content on a user’s news feed.

The photo and video-sharing service, Instagram, has more than one billion active monthly users (Barrett, 2019). It is the third most popular social media network, after Facebook and YouTube. Barrett (2019) noted, “Instagram hasn’t received as much attention in the disinformation context as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, but it played a much bigger role in Russia’s 2016 election manipulation than most people realize” (p. 7).

The popular microblogging site, Twitter, is another social media platform that is awash with disinformation and propaganda campaigns (Hindman, 2018). By its nature, Twitter is ideally suited to be a user’s customized news aggregator. Research sponsored by the nonprofit Knight Foundation examined 10 million tweets from 700,000 Twitter accounts that linked to 600 known fake news sites.

With 1.9 billion monthly active users around the world (as cited in Mohsin, 2019), YouTube is the largest video sharing platform on the Internet. Users upload 500 hours of content to the site every minute (Hale, 2019). With these statistics in mind, it is impossible to believe that YouTube, which Google bought in 2006, is immune from the spread of disinformation.

Regardless of what social media platform people prefer, for some people, the truth may not matter. McIntyre (2018) explained that we live in a post-truth era, where “objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.” He argued that information could be introduced within a political framework to support one meaning of truth over another.

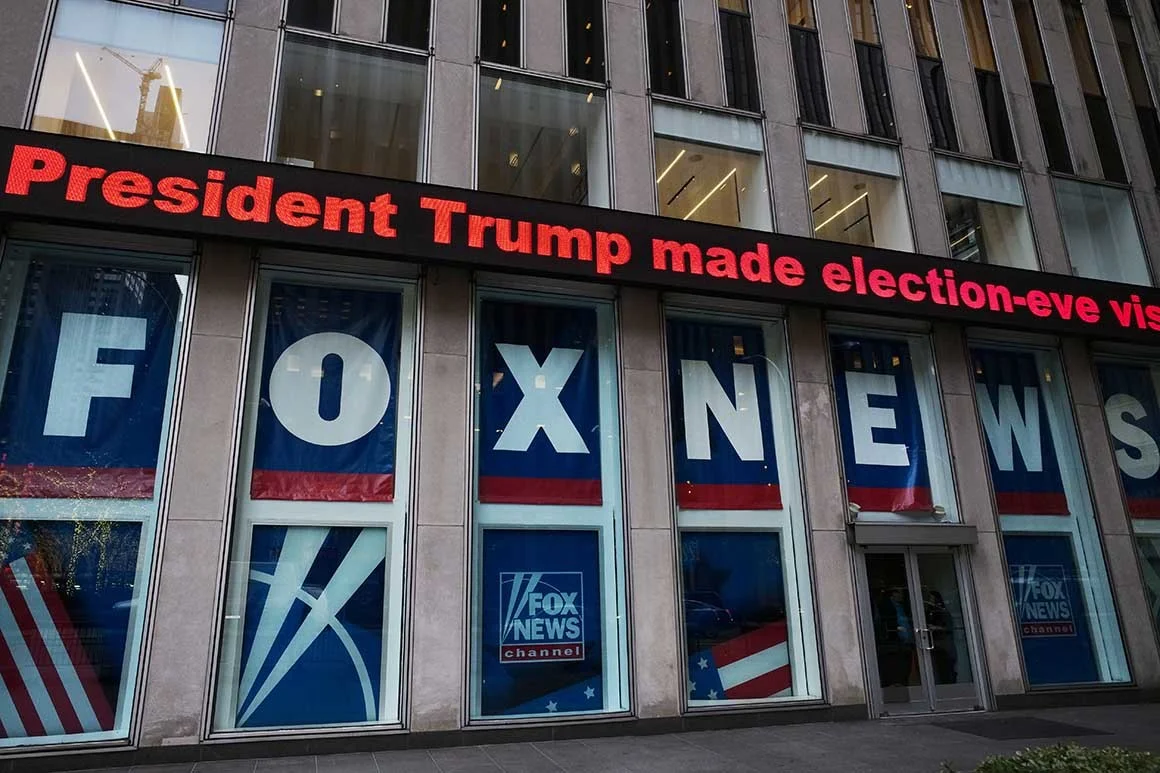

One place that conspiracy theories thrive is in far-right online outlets. For years, conservatives have branded the mainstream media as the “liberal media.” Starting in the 1990s, many Republicans began speaking openly about how the media were on the side of the Clintons (McIntyre, 2018).

Although no study has definitively proven that Trump won the election because of Russian meddling, all the studies I reviewed concluded that he was the primary beneficiary of fake news. Allcott and Gentzkow (2017) determined that “fake news was both widely shared and heavily tilted in favor of Donald Trump” (p. 212).

In the lead-up to the 2016 election, one of the most widely shared pro-Trump fake stories involved Pope Francis. The article featured a photo of the pontiff and the headline: “Pope Francis shocks world, endorses Donald Trump for president.”

There is a common misconception that those who create fake news are either Russian trolls or Macedonian teenagers. While that profile certainly exists, it does not tell the whole story. Indeed, some of the notorious creators spreading disinformation about American politics are living inside the United States.

As the public and the mass media have scrutinized the redacted release of special counsel Robert Mueller’s report on Russian interference in the 2016 election, there has emerged new information about the extent of Moscow’s involvement in trying to sway the vote.

As technology has advanced, a new front in the fight against fake news has emerged. Machine learning algorithms and artificial intelligence (AI) have given rise to so-called “deepfakes.” Chesney and Citron (2019) described these as “highly realistic and difficult-to-detect digital manipulations of audio or video…”

As the 2020 presidential campaign looms, there are concerns that disinformation will again be a factor in the election. According to Politico, the Democratic National Committee has warned all candidates to be prepared to avoid a repeat of 2016.